Why “words per minute” needs an update in 2026

If you’ve ever compared an English WPM score against a Chinese or Japanese one, you’ve probably sensed something was off. The classic WPM convention—counting a “word” as five characters, including spaces and punctuation—was designed around Latin‑script English, not CJK scripts or emoji‑heavy chats. By design, it bakes language bias into leaderboards. (en.wikipedia.org)

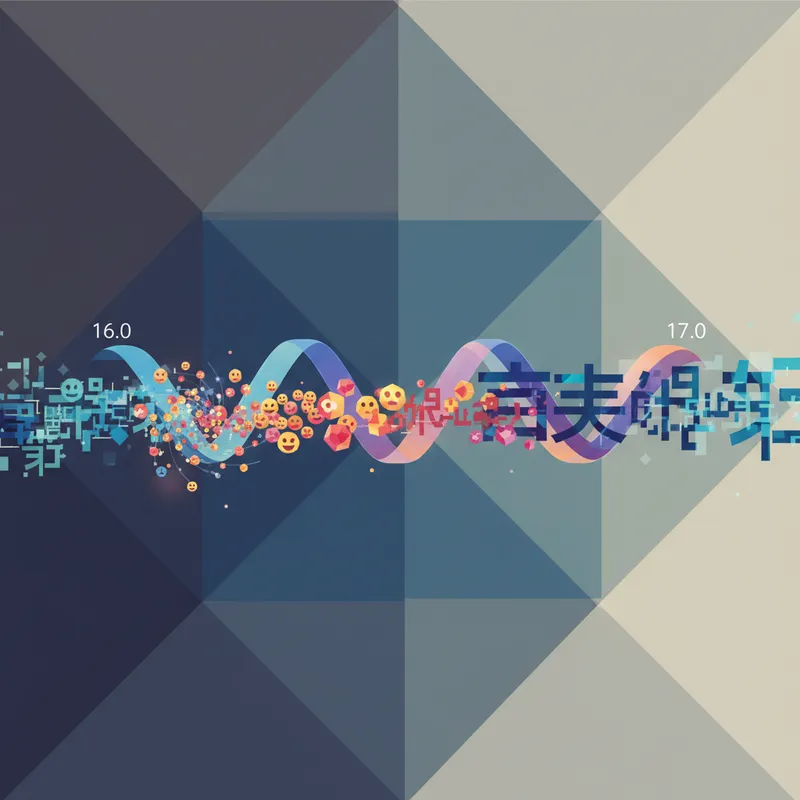

Meanwhile, the writing system itself keeps expanding. Unicode 16.0 (released September 10, 2024) added 5,185 characters and seven new scripts, bringing the total to 154,998 encoded characters—and even more CJK‑relevant metadata via 36,000+ new Japanese source references for ideographs. Emoji 16.0 added eight new emoji in total (seven encoded in Unicode 16.0 plus the Flag of Sark in Emoji 16.0). (blog.unicode.org)

Looking ahead, Unicode 17.0 shipped September 9, 2025 with 4,803 additional characters and four new scripts, and Emoji 17.0 is expected to land broadly on major platforms during the first half of 2026 (with some early support in late 2025). That means your test takers will soon encounter brand‑new emoji and scripts in everyday typing. (blog.unicode.org)

Bottom line: it’s time to make typing tests language‑fair.

What makes raw WPM incomparable across languages

- Different average word lengths: A standard “5‑char word” overestimates speed in languages with shorter orthographic words and underestimates it in agglutinative languages or those with longer words. Research across 17 languages shows big variation in words‑per‑minute—but characters‑per‑minute (CPM) is far more stable. (en.wikipedia.org)

- Tokenization differences: Chinese and Japanese traditionally don’t mark spaces between “words,” so “word” counting isn’t even well‑defined without NLP segmentation. (en.wikipedia.org)

- Input Method Editors (IMEs): Many CJK users type phonetics (e.g., Pinyin or romaji) and then select characters, adding extra keystrokes unrelated to the final characters shown. That inflates WPM for some languages and deflates it for others if you measure the wrong unit. (en.wikipedia.org)

- Emoji sequences aren’t single code points: Modern emoji often arrive as ZWJ sequences or flags built from multiple code points—but are perceived and edited as single “characters.” Counting raw code points will misrepresent difficulty and speed. (unicode.org)

A better scoreboard: CPM, graphemes, and bits

Here are practical, build‑today scoring upgrades that make leaderboards fairer across scripts and emoji‑heavy prompts.

1) Make CPM the primary speed metric

- Report characters per minute (CPM) as the headline number; show WPM as a secondary view (CPM ÷ 5 for English familiarity).

- Why CPM? Cross‑language evidence suggests CPM is a more stable measure than WPM, because WPM depends on language‑specific word length. (en.wikipedia.org)

2) Count what users perceive: grapheme clusters

- Measure speed in grapheme clusters per minute (GCPM) using Unicode Text Segmentation (UAX #29). Grapheme clusters align with “user‑perceived characters” across scripts (e.g., consonant + vowel signs in Indic, or a whole emoji ZWJ sequence). (unicode.org)

- Treat fully‑qualified emoji sequences as single grapheme clusters, per Unicode Emoji (UTS #51). This ensures a family emoji or a “person + skin tone” counts as one, just like users expect. (unicode.org)

Implementation tip: In the browser or app, segment the reference text into grapheme clusters up front (e.g., using Intl.Segmenter or a UAX #29 library). Score accuracy and speed by clusters, not code points.

3) Offer information‑theoretic normalization (advanced)

- Add an “info‑rate” score: bits per minute (bpm). Estimate the average bits per character of each test prompt using a language model or compression (lower cross‑entropy = fewer bits per character). Then: bpm = CPM × bits_per_character.

- Motivation: Spoken‑language research finds that, despite different syllable rates and densities, languages transmit information at similar rates (~39 bits/s). An info‑rate metric brings us closer to measuring actual cognitive/linguistic throughput rather than orthographic convenience. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Pragmatically, start by normalizing CPM with a fixed per‑language bits/character estimate from a representative corpus, and refine over time.

4) Keep “classic WPM,” but make it language‑aware

- If you must show WPM, compute it from GCPM using per‑language average “chars‑per‑word” derived from your own multilingual corpora rather than a universal 5. Publish the mapping for transparency.

- Always show CPM/GCPM alongside to avoid misleading cross‑language comparisons. (en.wikipedia.org)

Emoji‑inclusive prompts that reflect 2026 reality

- Include RGI emoji and common ZWJ sequences in prompts (family, professions, multi‑skin‑tone people, keycap sequences). UTS #51 defines which emoji/sequences are “recommended for general interchange (RGI)” and how they behave as single units. (unicode.org)

- Stay current: Emoji 16.0’s seven encoded emoji (plus the Flag of Sark in Emoji 16.0) rolled out across 2024–2025, while Emoji 17.0 is expected to appear broadly in early–mid 2026 across major platforms. Build your prompt pools and renderers to support both. (blog.emojipedia.org)

Practical tip: Validate that your editor input and rendering treat emoji sequences as single grapheme clusters—cursoring, deletion, and backspace should operate atomically. UAX #29 and UTS #51 set the ground rules. (unicode.org)

Multilingual corpora and transliteration fairness

- Curate parallel prompt sets across scripts (Latin, CJK, new Unicode 16.0/17.0 scripts) and difficulty tiers.

- For CJK, provide both native‑script and transliterated (Pinyin/romaji) test modes and label them distinctly on leaderboards; IME composition and candidate selection add overhead unrelated to final characters. (en.wikipedia.org)

- Localize emoji names/keywords via CLDR to generate natural, culturally appropriate prompts that mix text and emoji. (cldr.unicode.org)

Implementation checklist (for test builders)

- Segmentation

- Use UAX #29 to segment prompts into grapheme clusters; store cluster counts for accuracy and pacing. (unicode.org)

- Treat emoji sequences as one cluster per UTS #51; test skin‑tone modifiers, keycaps, and complex ZWJ sequences. (unicode.org)

- Metrics

- Primary: CPM and GCPM; Secondary: language‑aware WPM and optional info‑rate (bpm).

- Publish your conversion formulas and per‑language parameters.

- Prompt design

- Balance plain text, numbers, punctuation, and emoji based on real‑world frequencies; include a CJK set without spaces and with mixed emoji.

- Refresh annually to reflect new Unicode/emoji versions; Unicode 16.0 and 17.0 together added ~9,988 characters and multiple new scripts. (unicode.org)

- Input handling

- Don’t penalize users for IME candidate selection keystrokes; score against committed text timing instead.

- Transparency and QA

- Version your test content by Unicode version (e.g., “Unicode 17‑ready”) and document known platform emoji gaps during rollout windows. (blog.unicode.org)

Quick wins for typists (actionable tips)

- If you type in CJK with an IME, practice phrase‑level input so your IME predicts better and reduces candidate picks. (en.wikipedia.org)

- Mix prompts: alternate pure‑text sessions with emoji‑rich ones to build grapheme‑level rhythm (especially for ZWJ sequences). (unicode.org)

- Track CPM/GCPM as your main progress metric; treat WPM as a legacy display for English contexts. (en.wikipedia.org)

The takeaway

Unicode’s rapid growth—5,185 characters and seven scripts in 16.0, plus thousands more in 17.0—along with the 2026 wave of Emoji 17.0, makes old‑school WPM comparisons feel increasingly out of date. Shift to CPM and grapheme‑aware counting, consider an information‑theoretic score, and design emoji‑inclusive, multilingual prompts. Your users will get a fairer, more modern leaderboard—no matter what they type. (blog.unicode.org)